The Author - MORIZ SCHEYER

MORIZ SCHEYER

LIFE AND CAREER

LIFE AND WORK

Moriz Scheyer was born on 27th December 1886, to a Jewish family in Focşani, Rumania. His father was a successful businessman; by Moriz’s adolescence the family had moved to Vienna, where they lived in Hietzing, a pleasant suburb in the south-west. After secondary education at a Gymnasium (a traditional ‘grammar school’), he studied law at the University of Vienna, graduating in 1911. He began work on the staff of the Neues Wiener Tagblatt - one of Vienna’s two ‘quality’ daily newspapers - in 1914.

His attitude to the politics of that period is not clearly documented, although he did publish a poem on the horrors of the War in 1914. It seems that in any case a health condition precluded him from active service.

Some time before 1919 Scheyer made a long sea voyage, via Egypt to South America. This inspired a range of travel writings, which are collected in his first books: Europeans and Exotics (Europäer und Exoten, 1919), Tralosmontes (1921) and Cry from the Tropical Night (Schrei aus der Tropennacht, 1926)

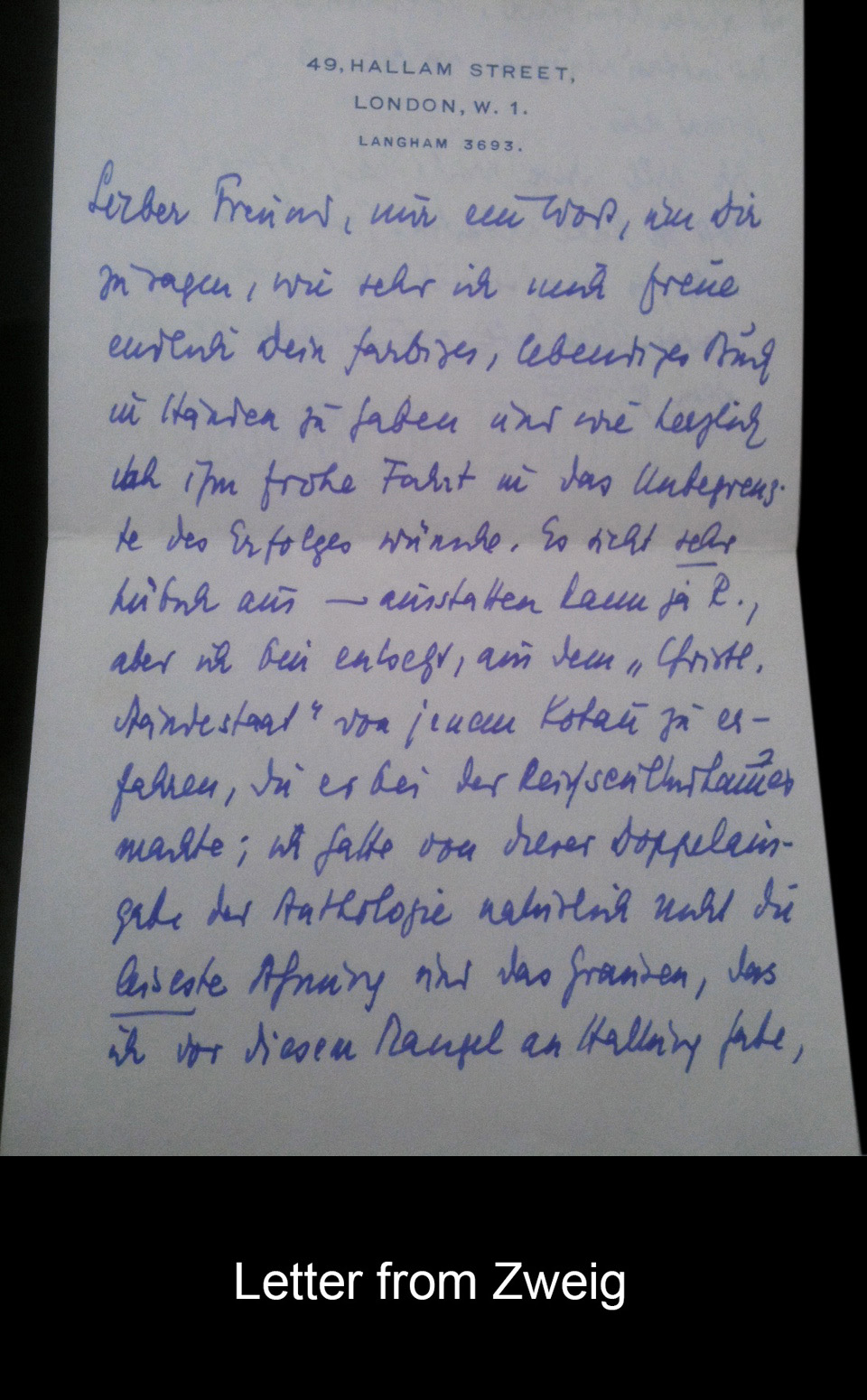

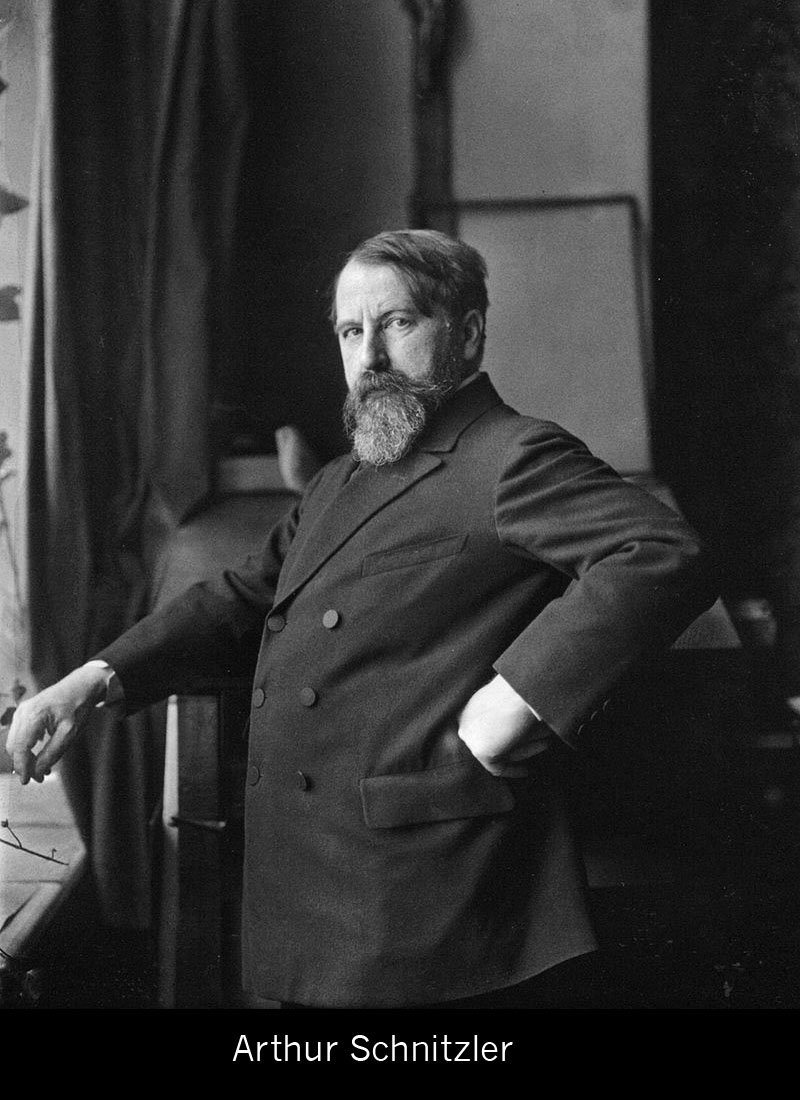

A lover of French culture and literature, Scheyer lived in Paris for an extended period before his return to Vienna in 1924, acting as a Parisian arts correspondent for his Viennese paper; and he continued to visit Paris regularly even after that date. He also seems to have spent some time as a correspondent in Switzerland. From 1924 until his dismissal in 1938, Scheyer was arts editor of the Neues Wiener Tagblatt. As head of ‘Theater und Kunst’ - the review section – he held a position of some cultural influence, and was acquainted with many of the most prominent writers and other artistic personalities of the time, including the celebrity conductor Bruno Walter and such authors as Arthur Schnitzler and Joseph Roth. He seems to have been particularly close to Stefan Zweig.

In 1925 Moriz married Margarethe (Grete), the daughter of a successful Czech-Jewish industrialist and widow of Bernhard Schwarzwald, a doctor who had run a sanatorium just outside Salzburg for patients with nervous disorders. It seems likely that the couple met through their mutual acquaintance Stefan Zweig. Through marriage Moriz acquired two adoptive sons, Stefan and Konrad (after emigration to Britain, Stephen Sherwood and Konrad Singer). The family - including Sláva Kolařová, Grete’s companion and the children’s nanny - settled in a comfortable apartment in the Mariahilferstrasse, near the centre of Vienna.

Scheyer wrote reviews of both plays (for one particular theatre, the Josefstädter) and books; but his main literary activity revolved around the feuilleton. This is a distinctively European genre of literary journalism - an essay, often taking a particular book, exhibition or other event as its starting-point, but extending beyond review to broader analysis or reflection. Scheyer’s favourite themes are usually literary or artistic figures or other great men, or indeed women, of the past.

Scheyer was dismissed from his post at the age of 51, at the height of his career, immediately after the Nazi takeover in March 1938. Forced to emigrate, abandoning home, money and possessions, he travelled with his wife to Paris, where he hoped to resume a literary career. His adoptive children, Stefan and Konrad, succeeded both in emigrating to Britain and in continuing their studies there.

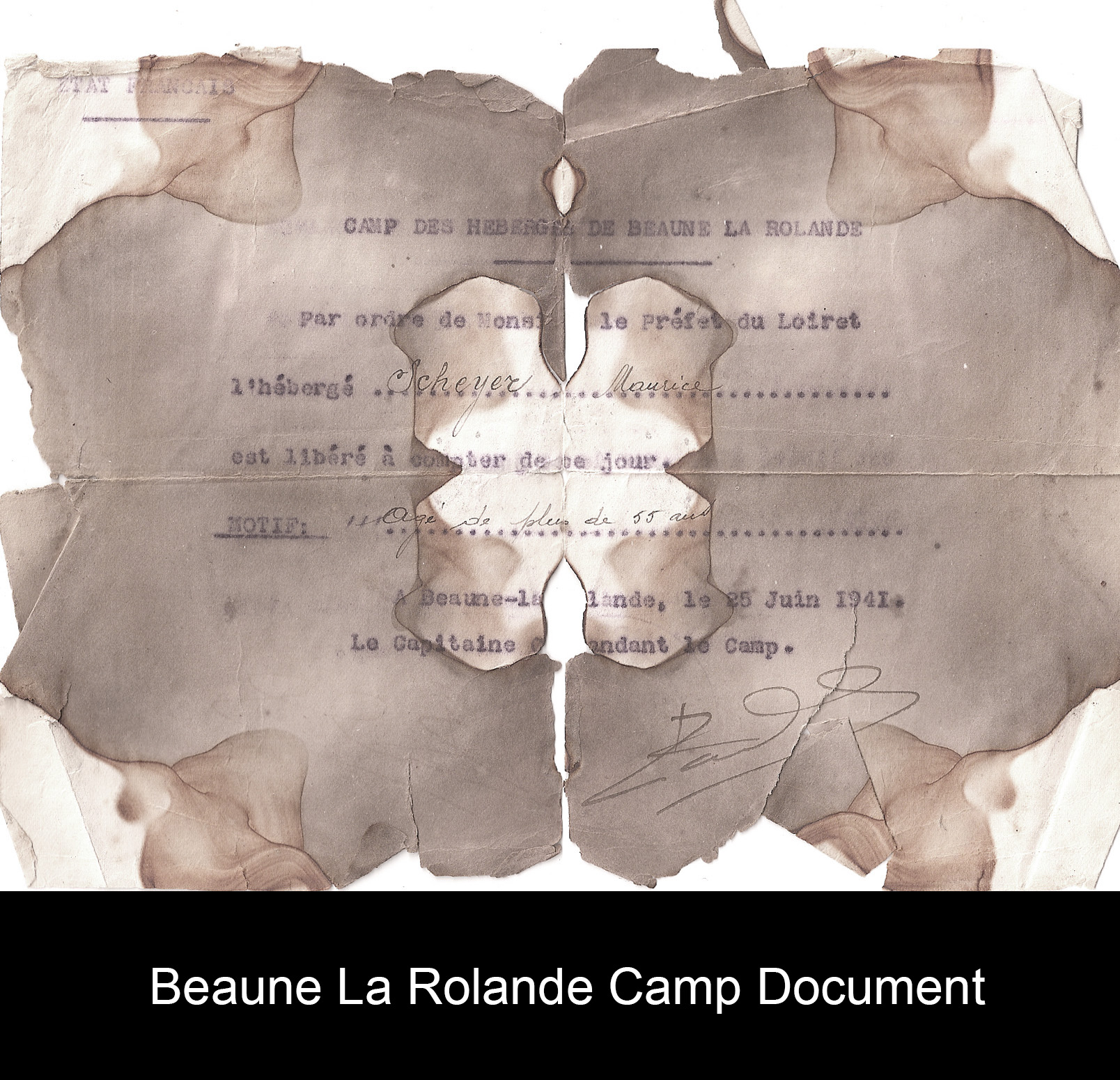

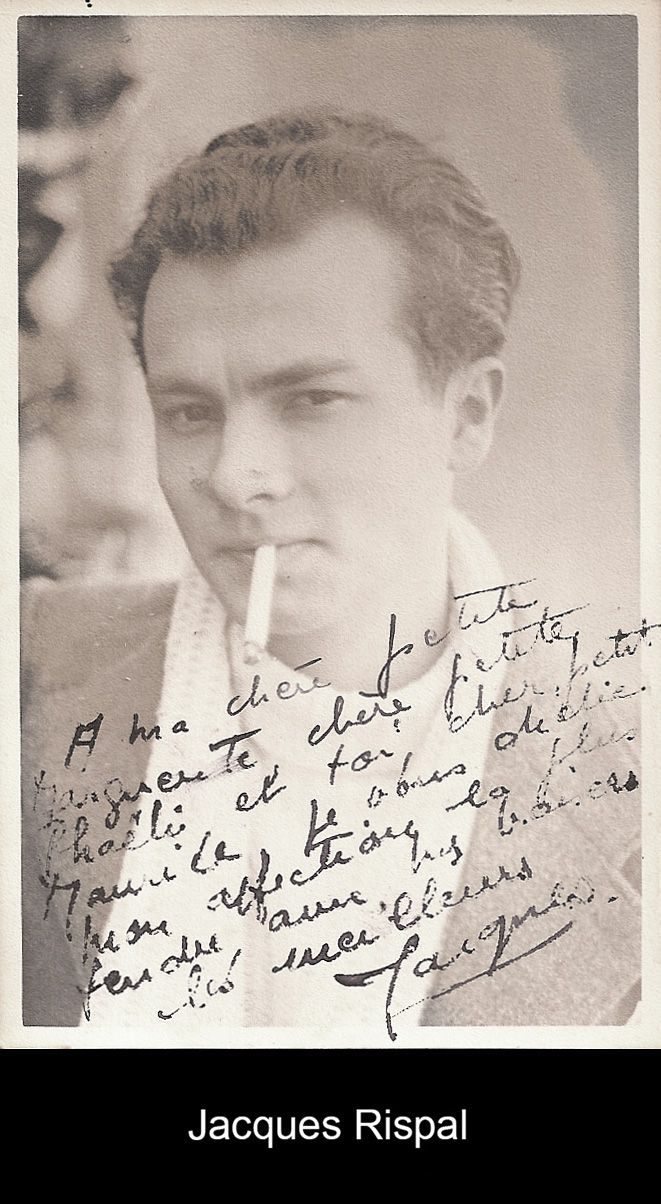

Moriz’s and his companions’ subsequent experiences in France - of persecution, flight, incarceration, attempted escape to Switzerland, rescue by the Rispals, a family involved in the Resistance, and clandestine life in a convent - are the subject of Asylum.

The book, discovered during a house move in 2006, nearly seventy years after the author’s death in 1949, is a unique document. Written in the heat of events, it is a vivid and devastating account by a first-hand witness and survivor - remarkable both for its furious emotional response and for its penetrating analysis of the Nazi persecution and of life and politics in occupied and unoccupied France.

LITERARY WORK

Moriz Scheyer’s first three books - Europeans and Exotics, Tralosmontes and Cry from the Tropical Night - consist largely of essays or stories inspired by his travels. (He also published some other travel writings in newspapers.) The books consist of vignettes, vivid depictions of unusual places, events and, in particular, characters.

For example, we meet Saadi ibn Tarbush, a young Egyptian boy who acted as Scheyer’s guide in Cairo, and to whom the glimpse given by Scheyer of the glamour of the European’s life turns out corrupting and fatal. Then there is Gly Cangalho, a morphine-addicted ‘Creole’ character who spends all her time travelling on cruises, and is known to all captains. Gly is a recurrent, apparently semi-fictionalized character in these early books, and seems to be the focus of some obsession on Scheyer’s part. Then, there are the parodic Englishmen - themselves almost exotic creatures in their ability to be at home everywhere and lack any emotional response to the exotic all around them. (The eccentric English also feature in an earlier piece of travel writing, where a couple on leave from India are wholly focussed on victory in a bob-sleighing in the Engadine valley.) Or, there is Mr Dronnink, a Dutch musical genius ruined by a woman and by drink, ‘burnt out’ and reduced to playing the piano on cruise ships. And we have vivid pictures painted of the experience of a tropical night on the ship; of storms, of cockfights, of the ‘coffee coast’. The characters seem straight out of the world of Agatha Christie; we only need an unexplained body or two to transform the already eerie atmosphere of the memoirs to that of 1920s crime fiction.

From 1924, as ‘Chef de Feuilleton’ for the Neues Wiener Tagblatt, Scheyer occupied a position of editorial authority, while devoting himself mainly to the writing of reviews and feuilletons.

The latter have certain typical characteristics: the creation of mood in a short span; the miniaturist’s attention to detail; succinct, punchy summing-up of an argument, or character; often some kind of emotional or ‘sentimental’, rather than purely analytical, response to the subject. Scheyer was at home with this miniaturist’s art; and he later brought some of it to bear, in a very different context, in his autobiographical work Asylum. There, chapters like ‘In place of a chapter on the Resistance’, ‘Carlos’, or ‘The undeserving survivors’, read rather like feuilletons - albeit with themes far from those of his earlier literary activity.

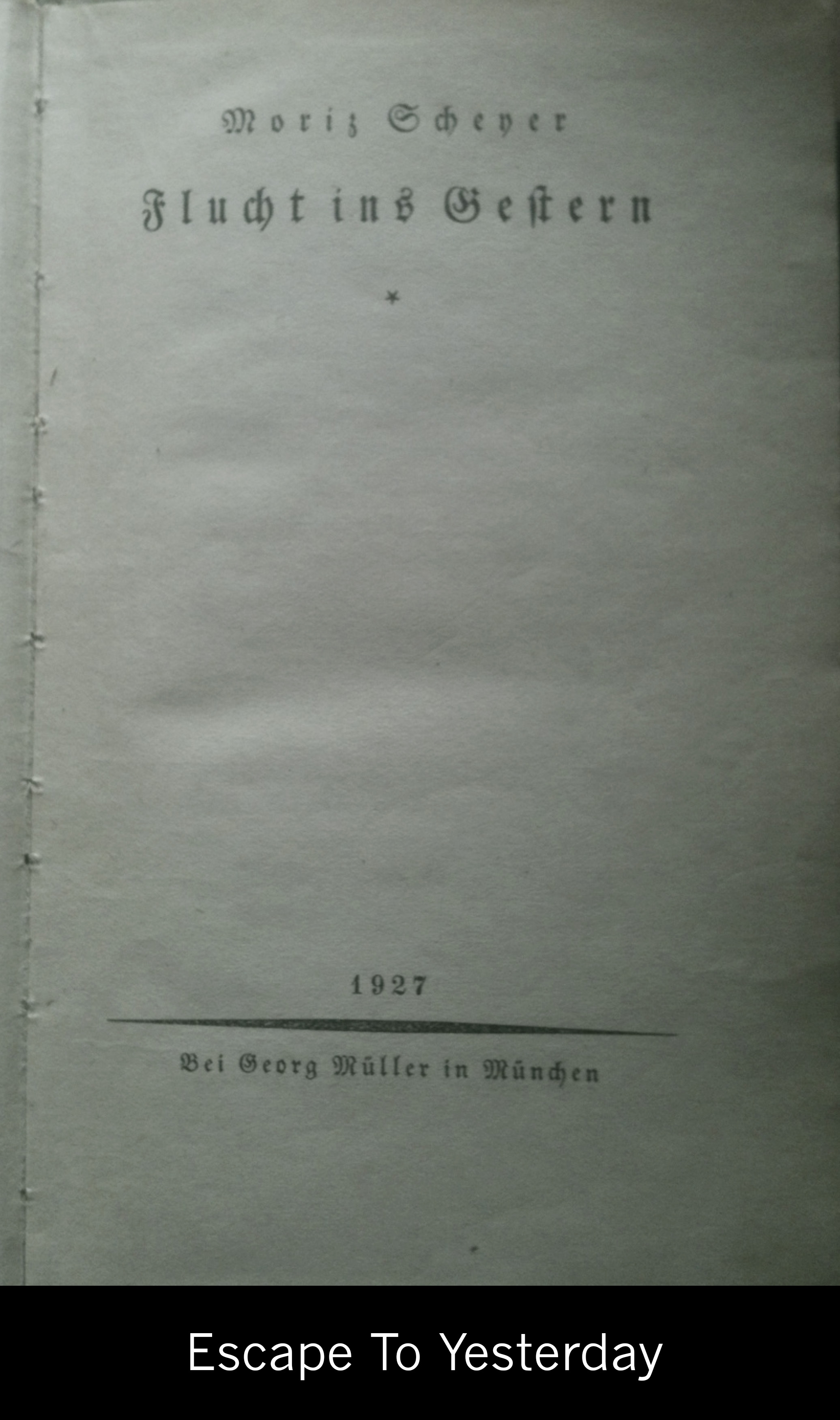

The three further books Scheyer published in his own lifetime were collections of such essays, which had previously appeared in the NWT. They are: Escape to Yesterday; Human Beings Fulfil Their Destiny; and Genius and its Life on Earth. (The last was published a few short months before the Anschluss, and in early 1938 was receiving a positive response in a range of newspaper reviews.)

The titles in themselves are indicative of certain moods or attitudes. The last two books reflect the author’s preoccupation with the notion of the ‘great man’ - or, occasionally, woman - and especially with that of the great artist. The first of the titles betrays his capacity for nostalgia.

THE LITERARY MILIEU: EARLY 20TH-CENTURY VIENNA

Both can be seen as characteristic attitudes, not just of Scheyer, but also of Viennese writing of the early twentieth century more broadly. They are attitudes which he shares, not least, with his almost exact contemporary (1881-1942) and friend, Stefan Zweig.

Much of Zweig’s literary output - his most substantial books, in fact - consisted of biographies of historical, literary or intellectual figures. Examples are his works on Balzac, Dickens, Dostoevsky, that on Romain Rolland, that on Casanova, Stendhal and Tolstoy. It is not just that Scheyer shared with Zweig the fascination with biography and with the great men of history, as well as tendency to see in the literary or artistic genius some more-than-merely-mortal individual; each of the above figures was also the subject of a feuilleton by Scheyer - in most cases, it seems, inspired by the previous Zweig publication. Scheyer’s last two books consist largely of essays dramatizing the life-stories of such ‘greats’; to the above names are added those of Verlaine, Victor Hugo, Baudelaire, Rembrandt.

Nostalgia is something of a Viennese literary speciality, in the early years of the twentieth century. The obsession with transience, with a vanishing, unrecoverable world, recurs in the writings of Hugo Hofmannsthal, in the novels of Joseph Roth (Radetzky March, The Emperor’s Tomb), obsessed with the loss of the Old Empire and its traditions, and in the short stories of Stefan Zweig. (Scheyer wrote an obituary of Roth – one of the few pieces he published after his emigration to Paris.)

In Zweig’s Buchmendel, an unemployable - but irreplaceable - man of letters is ejected from the café where he has for years resided, by the harsh utilitarian attitude of the new management; in Game of Chess, the mental breakdown of the brilliant amateur chess-player is in a sense the breakdown of the old world which he represents against the uneducated machine-like character of his opponent. (This character, Dr B., is in fact a royalist who is attempting to hide Austrian Imperial assets from the Nazis in the hope of a subsequent restoration.) Letter from an Unknown Woman is redolent with the sense of a lost past; and ‘The World of Yesterday’ provides the title of one of Zweig’s last books, in which he recalls in nostalgic detail the world of his parents’ generation.

So, too, Scheyer - in the context here of his older contemporary Artur Schnitzler - writes of a ’ … cultural-historical document. The reflection of a city, that has since lost its own “I”.’

Schnitzler’s Vienna – that world of tradition and culture, of clear social orders and customs, of elegant love-affairs – is gone; it is a ‘disappearing dream, the resonance of a memory. Perhaps it will soon be no more than a barren word, an abstract concept without reference’ (Escape to Yesterday, p. 176). One seems here to be sinking not just into nostalgia but into a potentially endless nostalgic regress. Schnitzler’s work – his portrayal of characters from across the Viennese social hierarchy, and of the mores and desires that connect them – is itself replete with nostalgia. The focus on transience, and the desire to revisit the past, are prominent features of Schnitzler’s characters, for example in his best-known play, Reigen (La ronde, or Merry-go-round), an interlocked chain of sketches depicting sexual encounters at all levels of Viennese society. Nostalgia is already an essential element in this poetic world for which Scheyer experiences nostalgia.

In Asylum, of course, one might say that Scheyer had good reason to be nostalgic. ‘Once upon a time …’, he begins - and proceeds to talk of the lost innocence of the world of 1944 – the impossibility of still enjoying nature, and the summer, as one used to before the War intruded (Asylum, pp. 207-9). But it is striking that he here quite closely echoes words written in 1927, in the preface of Escape to Yesterday; there, already, summers are not what they were.

Again, when he talks in Asylum (p. 216) of how it is the present that seems ghostly, and only the past seems real, the notion recalls perspectives in his previous writing:

‘Yesterday … it seems so many years since there still was a yesterday. It has become something so distant, so improbable, that – even if you have actually experienced it – you think of this yesterday as of a lost dream. … It is spring now; then it will be summer, autumn, winter; and then spring again. But all of that is seems distant and devoid of light; none of it has the capacity to touch you any more. The time of expectations is past. Beyond the realm of hope, of fulfilment, of beauty and excitement, we watch unmoved as a present which is at once harsh and ghostly passes us by – a present which is nothing but discontented noise and emptiness … between yesterday and today everyone has become a stranger to himself: more troublesome than even a dead man for the living …’

(Escape to Yesterday, pp. 9-11)

Nostalgia is a theme elaborated already in the preface to his first published book, where there is a focus on the healing power of memory, an obsession with transience, a sentimentality about the value of the moment.

‘… I have sought, again and again, to take refuge from the desolate reality of the last years in the only truth that still makes existence tolerable, opening wounds but at the same time healing them: memory’

(Europeans and Exotics, p. 5).

It may seem inescapable to see Scheyer, not just as an exemplar of Viennese literary nostalgia, but rather as a permanent malcontent. An extremely sensitive individual, easily hurt, nervous (although at the same time, clearly, one who was sensitive to the beauty, the excitement, of moments – of books, of musical experiences, of paintings, of relationships). In the reminiscence of him by his stepson, Konrad Singer, he was someone who simply found it difficult to be happy - a permanent pessimist.

There may, of course, be some concrete reasons for pessimism, in the volumes published up to 1927. One – though there are grounds for no more than speculation here – may be unhappiness in love. Moriz met Grete in, presumably, 1925, after the death of her first husband. A previous romantic obsession seems to be hinted at in Tralosmontes; and unhappiness in love is a submerged theme, at least, in the 1927 volume.

‘There is only one solution: to love. You can only rediscover that sunken island, your homeland, in the heart of another – no longer in yourself.’ (Escape to Yesterday, p. 11.).

In Europeans and Exotics, the end of the preface – talking of the comforts to be had from travel, and from the memory of it – also suggests a profound loneliness.

Another kind of misery is easier to document - namely that related to the Great War and its aftermath. Alongside some more general expressions of the dulness and emptiness of the present, the prefaces to both Europeans and Exotics and Escape to Yesterday contain some comments which are more historically specific.

‘These pieces were mostly written during the War, and intended for the NWT and other, foreign newspapers and reviews; they were written in the haste of the moment, but without belonging to that moment, with its debased, mendacious language. I felt it my duty as a “good European” to keep as far as possible away from any officially sanctioned “mindset”.’ (Europeans and Exotics, p. 5)

‘They have disappeared without trace – vanished in a puff of dull, suffocating smoke – those wonderful castles in the air, those bright Palaces of the Grail that were pointed out to us by cunning deceivers on the Horizon of Peace. They tricked us with the prospect of a resurrection from the mass graves of the dead as well as the mass graves of the living – and they ended up destroying our last illusions. Dynasties were overthrown; oppressors put aside; but in their place came a thousand other dynasties, a thousand other oppressors, each with a well-polished lie at the ready – a lie which was quite cynically deposited in the dustbin just as soon as the “last” fluctuation on the stock exchange of world history had turned the weaker into the stronger. People babbled of progress, made proclamations of freedom – but in reality every solemn phrase, every programme, every attack on the status quo – every form of progress – only really had the purpose of enabling the onward march of the Market. The ideology is balder and more omnipresent than ever, and there has survived but one ideal: ownership. For ever and ever – amen!’ (Escape to Yesterday, pp. 10-11)

The remarks attest to the profound disillusionment and despair that resulted, not just from the war itself, but from the disastrous Depression that followed it, in Austria in particular.

Scheyer is speaking of the illusory hopes that political leaders raised for the post-War world. Certainly there seems to be a nostalgia for the ‘old order’ in preference to rampant capitalism; it would also be possible to interpret the words in a more definitely socialist manner. Another work of Zweig’s - his posthumously published The Post Office Girl - again helps us understand the emotional background. It is a searing account of the misery infllicted on ordinary men and women in the aftermath of the Great War. Veterans of the war, as well as bereaved dependants, have no economic possibilities, and insignificant support from the state. Livelihoods are lost in a moment; a life’s, or indeed generations’, investments rendered worthless overnight. In Zweig’s book - as presumably also for Scheyer - society is to blame, and certainly also the political leaders of the time. But this is no political tract; there is no agenda or solution proposed.

It is interesting here to consider Scheyer’s political attitude to the First World War itself. A poem was published by Scheyer in the Arbeiter-Zeitung (the organ of the Austrian Social Democratic party) on 17th November 1914:

Lonely Battlefield

Under the pale first snow

Many a young sorrow lies buried.

The late moon, indifferent and cold,

Shines down like a funeral torch.

The night utters prayers for the dead.

In the east there glimmers a distant light.

(Einsames Schlachtfeld

Unter dem bleichen, ersten Schnee

Liegt begraben viel junges Weh.

Der späte Mond, gleichgiltig und kalt,

Wie Sterbekerzen herniederstrahlt.

Die Nacht die Totengebete spricht;

Im Osten fröstelt ein fernes Licht.)

Scheyer (like Zweig) had been an ardent admirer of the pacifist Romain Rolland, and of the anti-nationalist philosophy of the ‘good European’. There seems insufficient evidence as to whether he remained a committed pacifist during Austria’s involvement in the war; certainly the above poem, written so early on in the hostilities, makes a powerful statement.

It is also noteworthy - and horribly ironic - that Scheyer’s last published volume, completed in 1937 and published in 1938, has much less sense of the ‘terrible times’, and the ‘need to escape’, than any of the others. But this too is revealing. Life was pretty good: he had a stable, respected professional position and was economically comfortable. And the advent of Hitler in Austria, though feared, was simply not anticipated as an immediate threat. Scheyer even received a letter from a senior colleague, in 1938, congratulating him on the publication of his book and anticipating a successful year ahead.

MORIZ SCHEYER AND MUSIC

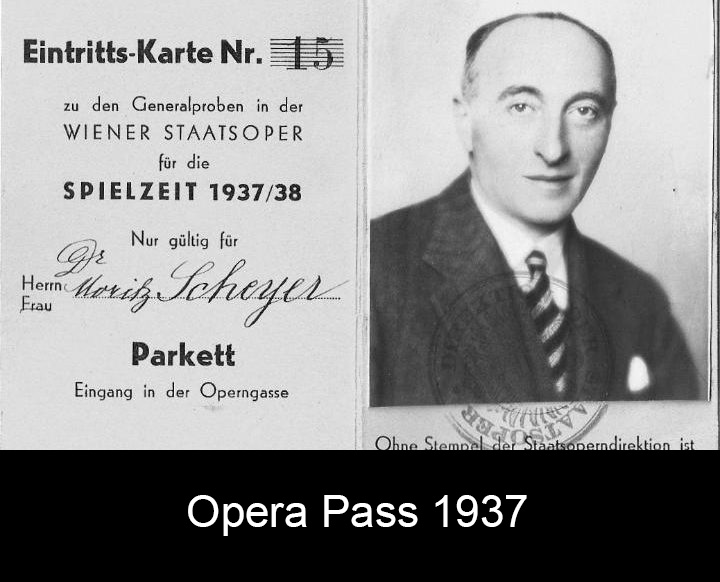

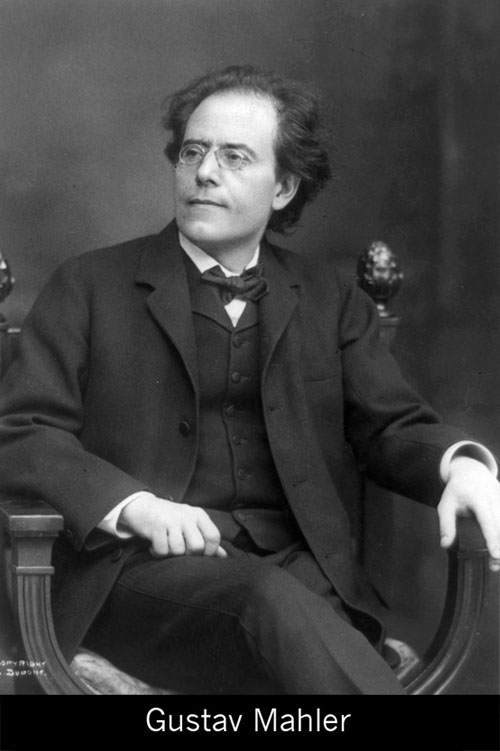

Scheyer’s attitude to and involvement with music also have to be understood in relation to their time and place. It is, I think, difficult for us to understand how fundamental music is in this culture, not just in artistic but also in social and intellectual terms. In Vienna classical music and its practitioners and institutions - especially the opera - were the focus of enormous popular fame, rivalries, and press interest; but, more than that, to intellectuals music was a pursuit with a moral, even religious, dimension, its practitioners, in particular the composer and conductor, godlike figures, whose realm of activity lifts them far above normal human endeavour. It is noteworthy that Scheyer, though not actually a music critic, had a pass to attend dress rehearsals at the Opera. A family anecdote has him addressing Gustav Mahler in the street, and he seems to have been friendly with Bruno Walter; for both of them he clearly had enormous admiration.

Music recurs as a metaphor in his writing, too: the sound of Nazi boots provides ‘the new theme tune of Parisian life’ (Asylum, p. 58); and in the camp at Beaune there is the ‘nightly symphony of misery and sorrow, with the rustling of straw running through it like a pedal note on the organ’ (p. 95). Such elaborate metaphors could also be paralleled from the writings of Zweig – whose musical obsessions extended to the acquisition of manuscripts of the great composers, as well as a desk that had belonged to Beethoven.

The rediscovery of music at Labarde, via the radio, is one of the most vivid emotional experiences in Asylum (pp. 179-82). Nowhere is his nostalgia more real than in the evocation of the vanished faces of Mahler - ‘the noble, illuminated face - the devotee at the altar of genius’ - and of a previous generation of performers at the Vienna Opera. Music has the capacity to take him back, but also to take him completely outside normal reality. An other-wordly vision, as he says, which at the same time can shed light on this world.

WRITING AND REAL LIFE

There seems a terrible retrospective irony, as one reads through Scheyer’s collections of essays, with regard to two of the recurrent themes of his work: that of ‘becoming great through suffering’ and that of women who sacrifice themselves for the men in their lives. Tolstoy, Wilde and Verlaine, for example, are characterized as achieving their true potential - fulfilling their destiny - through suffering. It was, very specifically, Verlaine’s period of imprisonment that brought out his greatness; Wilde’s turned him into a poet. (Genius and its Life on Earth: ‘Verlaine’, pp. 90-100; ‘Leo Tolstoy’, pp. 101-13 and ‘Oscar Wilde’, pp. 114-22.)

As for the women whose lives of self-sacrifice excite Scheyer’s interest, they include Mata Hari, the Empress Eugenie, Lady Hamilton (who inspires Nelson to greatness but dies lonely and unknown), Rachel (a famous French actress exploited mercilessly by her family), two literary figures, Mariana Alcoforado and Marceline Desbordes-Valmore, whose sorrows are sublimated in poetry, and Anna Grigorievna and Sophie Andreevna, who sacrifice their lives to Dostoevsky and Tolstoy respectively. There are, conversely, various female villains or adventuresses - Verlaine’s wife, the Tsaritza Catherina. (Human Beings Fulfil Their Destiny: ‘Sophie Andreevna’, pp. 137-50; Escape to Yesterday: ‘Anna Grigorievna’, pp. 74-83, ‘Lady Hamilton’, pp. 200-11.)

On the one hand, all this may seem to belong to the realm of atavistic and historically unrealistic romanticizations of the great personalities of history and literature - and of an old-school, ‘harridan-or-heroine’, attitude to women. On the other, it may seem too horribly close to the bone, in relation to the very real suffering, heroism and female self-sacrifice that were to become so central to his own story.

At least it must be said that that in the real-life account, Scheyer is acutely conscious of the real-life heroism and self-sacrifice of two women in particular - Sláva Kolářová and Hélène Rispal; also - though less explicitly, and though he never mentions her by name - of his own wife, Grete. And of the self-sacrifice of the Sisters of the convent who take them in, which he describes in moving detail (Asylum, pp. 164-9).

Also that - again with the cruel judgement of hindsight - Scheyer’s main literary output, consisting of some 250 feuilletons, as well as sundry theatre and book reviews, all for immediate publication and consumption, may seem to today’s reader like a literary preparation, a honing of the talents required for the present work. The one which struggled to make it from writing to publication - indeed, to survive at all - but the one which, surely, provides his most enduring testament.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(1) Books by Moriz Scheyer Europeans and Exotics (Europäer und Exoten), Strache, Vienna, Prague and Leipzig, 1919 Tralosmontes: von Fernen und Schicksalen, Amalthea-Verlag, 1921 Cry from the Tropical Night (Schrei aus der Tropennacht), Georg Müller, Munich, 1926 Escape to Yesterday (Flucht ins Gestern), Georg Müller Verlag, Berlin, 1927 Human Beings Fulfil Their Destiny (Menschen erfüllen ihr Schicksal), Krystall- Verlag, Vienna and Berlin, 1931 Genius and its Life on Earth (Erdentage des Genies: ausgewählte Essais), Herbert Reichner Verlag, Vienna, Leipzig and Zurich, 1938 Asylum (Ein Überlebender), English trans. with epilogue by P. N. Singer, Profile Books, 2016

(2) Moriz Scheyer: Other Journalism Reviews and feuilletons in Neues Wiener Tagblatt, various dates 1919-1937; archive in Austrian State Library.

(3) Other Relevant Reading Georges Duhamel, Correspondance: l’anthologie publiée de Leipzig, ed. C. Delphis, Leipziger Universitätsverlag, 2001 Georges Rebière, Aimez-vous cueillir les noisettes? Message personnel, PLB éditions, 2012 Jacques Rispal, De la DST à Fresnes, ou trente et un mois de prison, Écomusée de Fresnes, 1990 Joseph Roth, The Radetzky March (Radetzkymarsch, 1932), trans. Michael Hofmann, Granta Publications, 2002 Joseph Roth, The Emperor’s Tomb (Die Kapuzinergruft, 1938), trans. John Hoare, Hogarth, 1984 Arthur Schnitzler, Reigen (La Ronde), 1897. Arthur Schnitzler, Youth in Vienna (Jugend in Wien), 1968 (posth.). P. N. Singer, ‘Moriz Scheyer: Writer’, in Moriz Scheyer, Asylum, pp. 282-92 Friderike Zweig, Stefan Zweig, English edition, Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1946 Stefan Zweig, Romain Rolland: The Man and his Work (Romain Rolland. Der Mann und das Werk, 1921), trans. Eden Paul and Cedar Paul, Allen and Unwin, 1921 Stefan Zweig, Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy: Adepts in Self-Portraiture (Drei Dichter ihres Lebens. Casanova - Stendhal - Tolstoi, 1928), trans. Eden Paul and Cedar Paul, Plunkett Lake Press, 2011 Stefan Zweig, Buchmendel, 1929, English trans. in Selected Stories, trans. Anthea Bell, Eden Paul and Cedar Paul, Pushkin Press, 2009 Stefan Zweig, Three Masters: Balzac, Dickens, Dostoevsky (Drei Meister. Balzac - Dickens - Dostojewski, 1930), trans. Eden and Cedar Paul, Plunkett Lake Press, 2012 Stefan Zweig, Chess (Schachnovelle, 1943), trans. Anthea Bell, Penguin Books, 2006 Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday (Die Welt von Gestern, 1943), trans. Anthea Bell, Pushkin Press, 2011